INTERVIEW

The origin of Enchanted Modernities

In 2014, the ground-breaking exhibition Enchanted Modernities charted the way Blavatsky’s Theosophy impacted the art of the American mid-West, influencing such artists as Agnes Pelton, Gordon Onslow Ford and Beatrice Wood. In this interview the editors Sarah V. Turner, Christopher M. Scheer & James G. Mansell discuss the origins of the project – now a major book – with FULGUR’s Ellen Hausner.

EH: Maybe we can start with each of you introducing yourself and saying a little about your research and your focus.

Sarah: I’m Sarah Victoria Turner. I’m an art historian and Deputy Director for Research at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, but before my current position, I was a Lecturer in the History of Art Department at the University of York. And it was whist I was at York that we started the Enchanted Modernitiesproject. Personally, I’m really fascinated by the intersections between the visual arts and Theosophy. This interest was first developed whilst I was working on my PhD, and this going back quite a number of years, and one of the chapters of my PhD was about a group of artists in early 20th-century London who were all members of the Theosophical Society. They set up a magazine together called Orpheus which published ideas about ‘imaginative art’. So I started from there and this one artistic group, and then continued to delve deeper into the world of Theosophy and the arts. I started to look for other people who were working on this subject—and that’s how I met James and Chris.

Chris: I’m Christopher Michael Scheer, Associate Professor of Musicology at Utah State University. My PhD dissertation was on the British composer Gustav Holst, who had a number of intersections with Theosophy and the Theosophical Society in London in the early part of the 20th century. After I started working at Utah State, I was lucky enough to receive a Leverhulme international fellowship based at Liverpool Hope University for a year. It was there that, along with a colleague who’s part of our network, Rachel Cowgill, I met James and Sarah, and became aware of an archive that was at the University of York—the papers of Maud MacCarthy and John Foulds that we all had interest in. That’s how we started working together on this Enchanted Modernities project. As we have the study of Theosophy and esotericism as it intersects music has become a greater part of my research world.

[L-R] Christopher M. Scheer, James Mansell and Sarah V. Turner. Courtesy of Utah State University.

James: I’m James Mansell, Associate Professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Nottingham. I would describe myself as an accidental researcher of Theosophy. It’s not something I set out to do exactly, but it’s followed me all the way through my career in one way or another. I discovered my interest in Theosophy by accident really, working on my MA thesis. I decided to research a composer who I thought was interesting called John Foulds. He was interesting to me because I was in Manchester and he was from Manchester. Starting from there I just found a fascinating trail of influence of Theosophy, not just in the work of John Foulds, but in a whole network of people who are connected to him in one way or another, including Maud MacCarthy, who Chris has also researched. And from there, I’ve just not been able to shake off my interest in Theosophy, even though I wasn’t particularly planning to pursue it. I did a PhD on the intellectual history of sound in the early 20th century and found that Theosophy was a major influence on people thinking and working on modernist experimentation and interactions between musical and visual arts, around the turn of the 20th century and through the early 20th century. Following that, my PhD morphed into a book about noise dealing more broadly with sound and soundscapes in early 20th century culture where again, Theosophy and its intellectual power was present. So I would say that wherever I’ve looked, I’ve found that Theosophy was a major intellectual and cultural current in the early 20th century. A lot of historians who have worked on these kind of areas before me and us have tended to overlook this, for one reason or another, but I found it fascinating and just carried on pursuing it.

EH: My next question is about how the project came to be. Chris you mentioned briefly about the grant going to Liverpool, but can you say a bit more about the whole project and whose brainchild it was and how it come about?

Chris: Sure, and hopefully Sarah and James will chime in when I get things wrong! But it as I mentioned before it started in Liverpool where Rachel Cowgill and I were working together. We read this article by this upstart cultural historian of sound named James Mansell about John Foulds. And we were like, woah, what’s up with that?! And so we needed to meet him, and we did—he was just over in Manchester—and started talking about Theosophy and music, and James said ‘oh, I know these other people I just met at a conference who are art historians who are working on the same thing!’ (Sarah Victoria Turner and Helena Capkova) And we kind of decided after talking as a group that we should have a one day symposium at Liverpool Hope, which is really I think what we could say was the beginning of this project: organising it together, inviting people from around the world who were also looking at the influence of Theosophy in the arts to present on that day. And one of the outcomes of that day after discussion with participants was the need to see if we could create a network with the work we were doing and the connections we were making—and so we applied for a Leverhulme networking grant. We were lucky enough to be successful in getting a networking grant from the Leverhulme, and that brought a number of universities and scholars who were working in the area of Theosophy and the arts together to pursue a proposed three-year slate of activities around the world.

Sarah: We realised this was such a big topic, and as James has said as well, so much of it had been relegated to footnotes and, as a result, whole archives, whole careers, had been ignored. And what we found was that we were coming across the same problems from our different perspectives: as art historians, historians of religion, literary scholars, musicologists and so on. And so we realised that this way of organising a research network was the most productive route forward to kind of explore that cultural complexity of Theosophy and its cultural influences—because we realised the topic was so rich and so massive and there was so much to do! And then there was the sense that we wanted to explore this research through different formats as well—we could already see exhibitions forming in our mind, and then Chris was saying well, there’s so much great music out there, how about we do a concert series and some talks around that?—you know we had all of these ideas. So we had to find a way to sort of put it all together and organise this research internationally over several years. That was the exciting challenge of working on this topic–there was so much to do, but we had to figure out how practically could we do it and collaborate together.

EH: It’s quite fascinating because the project does have so many different aspects to it: an exhibition is a very different animal than a book. And I was wondering if any of you had perspectives about that, about if it forced you to think in different ways, or if you had to approach it in very different ways, because it’s such a different type of medium. Did anyone have any comments about that?

James: I think maybe one way of describing what we did was exhibition as research methodology. It wasn’t exactly the outcome, it wasn’t the endpoint of our research, but the exhibition was a tool or a way of actually doing the research, actually delving into the questions that we wanted to answer because it allowed us to access collections and think through the connections between different media and different forms of art: the connections between painting and music and film, for example. It was a way of asking and answering questions in the research, and I think actually doing the exhibition allowed us to see connections that we wouldn’t have seen otherwise.

EH: Yes, and the book is not a catalogue, in fact: it’s an extension, it’s a continuation of research, it seems.

Sarah: Yes, for practical reasons, and mainly because of time pressures, we couldn’t produce a catalogue to coincide with the exhibition. But I’m really pleased that we waited, and as James said then we could pursue that idea of exhibition as research. Because we not only had the exhibition, but we organised another symposium at the same time as the exhibition so we could more bring people with expertise in Theosophy and the arts together. We had the symposium in the actual exhibition, so we had all of these amazing artworks in conversation, in dialogue with the scholars, with the researchers that were talking about them. And those people are the people who became the authors in the book. Everything that we’ve done really has been conceived as a gathering of new ideas and around the idea of building up a dialogue about both the potentials and the challenges of thinking about the cultural importance of Theosophy. The book has given the exhibition a different afterlife as well I think. I’ve worked on a number of exhibitions, and you’re always sort of geared up to the end goal of having the exhibition and the catalogue ready at the same time, and it happens and the doors close, and that’s it. But this is a different way of working and it seems to have extended the life and the thinking around the project as well, I’d say.

Chris: If I could add too: in addition to the symposiums that were going on while the exhibition was up, we also had a number of concerts. And those are also represented in the book by a chapter on Dane Rudhyar and one by Christine Odlund. She came and actually walked through the exhibition, as well as giving a concert of her own music in the gallery space with these artworks on the wall. We learned a lot from putting the exhibition on in terms of how to shape different narratives, what narratives are important, how different narratives relate. I think between a book and an exhibition that’s one thing we can see is a commonality, and as Sarah and James have said, we learned so much from the experience I think that feeds into the book, as a result of those experiences.

Enchanted Modernities, opening reception, 2014. Courtesy of Utah State University.

EH: If I could just move to the content of the book—and I guess this is sort of the Big Question in a way–why do you think esotericism or occultism in general, and Theosophy in particular, has been ignored or downplayed in mainstream modernist art history? Sarah, in your essay you even wrote it has been ‘written out’. Why do you collectively think that this is the case? Why is this a silent narrative?

Sarah: It’s a big question! I think there are all sorts of institutional and disciplinary reasons to do with the way that academia in particular has been formed around certain narratives. But the one thing I would say is that this is changing so rapidly. And we’ve seen that made manifest through the popularity of exhibitions such as Hilma af Klint at the Guggenheim recently and all the other iterations of that exhibition around the world, and also a growing number of conferences and events focusing on new research about esotericism and the arts. So I’d say that whilst there is a narrative about 20th century—especially I’m thinking here about visual arts— when there was such an emphasis on the formal work of art, and a narrative of formalism that said ‘what happens outside of the frame isn’t interesting, we’ve got to concentrate on the work of art’s formalist attributes’. And so things like the real lives, the politics, the histories of objects and the people who made them fell out of view, really, especially within the canonical views of modernism which tended to be very much written around white male painters (to put it very crudely). And so all these other histories, they didn’t have room institutionally I think, within museums, within galleries, within books, and so I think that those are the big structural reasons why some of these other narratives about who contributed to the development of modern art have been somewhat sidelined. And I’m sure there’s lots that James and Chris can add more eloquently as well!

Chris: I’m not sure about more eloquently!—but it seems from the musical point of view, considering modernism as a way of thinking in the 20th century, it seems to have been for a long period of time predicated on disenchantment: this kind of analytical, logical, rational view of the world, and a view of the world which is innately negative. One might understand some of these esoteric and occult movements and their philosophies and beliefs as being set up almost in diametric opposition to those views. And so the artworks that are inspired by those ideas naturally come into conflict with traditional narratives of what modernity is—and that includes music. And so there was a tendency for works inspired by enchantment—as Sarah has said, this is changing so rapidly and so wonderfully—to be discounted or dismissed as not as serious, or somehow irrational and so not worthy of real attention.

James: I think you notice, when you read mainstream history, or art history, or music history, there’s what I can only describe as a footnoting of the spiritual. So when you read about a number of the figures who we were dealing with in the exhibition and the book, there’s a tendency to acknowledge that there’s an interest in the spiritual in a general sense, but that somehow that interest in the spiritual is not centrally relevant to the work or to the life of that individual or that movement. And the spiritual, I’ve noticed, is often treated in a very general way, so there isn’t an unpacking of different kinds of spiritual and religious interests that were at the heart of many of the modern art movements that we’ve been interested in. It’s almost to suggest, I think, that the religious and spiritual is somehow private in contrast to the public nature of the work and the movements, which I think for all of us really doesn’t do justice to the extent to which that the artists and movements that we’re interested in actually foregrounded the importance of Theosophy in our case, but also other kinds of spiritual movements, which, although related, were diverse and distinct. So I think what we were trying to do was to put back that foreground, to give it its place in the genesis of the works and the movements that we were interested in, in contrast to mainstream history that describes in a bracket or footnotes the spiritual in a general sense.

Chris: If I could add one more thing: specifically related to the book and the larger project, there is the still a lingering animosity between the left and right coast of the United States, which also no doubt plays in somewhat to these conceptions of where esotericism and occultism fits in American art; because in many ways it’s very much considered a West Coast thing. For a long time that meant it could be more easily dismissed, as I understand it, both in musical and art history.

EH: If I could just ask James, when you say private versus public: do you think that’s part of the reason that esotericism is taken more seriously now and is more of an academic subject, as the world in a way is more willing to investigate private things publicly?

Enchanted Modernities, opening reception, 2014. Courtesy of Utah State University.

James: I think that’s certainly part of it; I think that probably all of the different contributors to our book and to our network more widely will have had their own reasons for embracing this. But I think for me it’s just so obviously important. For me it’s not that I’m particularly motivated by an interest in the private especially, but I’m interested in giving a voice to something that was so obviously important to the people I’m researching, and I have no particular agenda to squash it. So for me it’s just a case of doing justice to the source material, where Theosophy is so obviously present. I think probably generally there’s been a move towards recovering these sorts of movements, because I think in general we are a bit more open and willing to research a wider array of intellectual traditions that may be in conflict with our own. But I’d be unwilling to answer for all people working in this field, certainly for the various people who contributed to the book. But for me it was a case of really giving a voice and shape to something that I found to be present in the archive and that had not been sufficiently accounted for by other historians.

Sarah: I think that’s the nice thing about a collection of essays as well: it has the possibility to hold all those different perspectives. Of course, there are three editors, and we want to convey the central argument of the cultural importance of Theosophy to the arts and the American West, but within the range of essays we wanted that kind of plurality of approaches, whether that be about different artistic media, or different levels of Theosophical thinking and commitment as well. Not all the artists in the book are by any means Theosophical Society members, they’re definitely not all signed-up, card-carrying members; but that doesn’t mean to say that Theosophy didn’t come very powerfully into their artistic worlds, and influence their thinking. So I think having that collection of many voices allows us that range of opinion and that range of possibility. And there is critique as well—we don’t want it to be a kind of straight-forward celebration. A lot of the essays are quite critical, and that’s important as well. It has that register and that texture running throughout the book.

EH: Sarah, do you have any particular idea yourself about why esotericism has become more acceptable within academia?

Sarah: You know, it’s really hard to pinpoint one thing, but I do think the growth of really serious, pathbreaking scholarship on women artists and cultural figures is one huge reason. And I think that has contributed to this quite serious shift in focus. And again, it’s bringing names into the light that have been ignored. And we can now see that they’ve been ignored for no good reason, apart from either their gender or their beliefs. And so I think that has a serious impact on the shift. Also, there is increasingly a more international focus within research in the UK and within America, and in the West more generally, and I think accounting for these movements that were global and international in their foundation has been quite a significant reason in this opening up of scholarship; and the serious and rigorous reassessment of the global movements of esotericism.

EH: And Chris, would you have anything to add in terms of the beginning of a great interest in esotericism on a serious academic level?

Chris: I would only add that that from my point of view, as I mentioned earlier, there seems to be something in also the kind of breaking down of narratives about modernism, and what modernity is, such that it isn’t talked about as one thing but as many things, and allows many different things to articulate what it is was to be living in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. And when we start getting that kind of polyphony of voices being allowed into the academy—not just about occultism, but about gender, about sexuality, about a number of things—we start to see, in my opinion, a much better picture, a better understanding of those times for us here presently than the kind of monolithic narratives of earlier times allowed.

EH: So another question I have is about Theosophy, which is of course the central theme of this and in the title. It had enormous influence, as everyone has pointed out, but there are many other traditions named in the book. Sarah, you mentioned Zen and an interest in indigenous cultures; many of the artists were not members of the Theosophical Society. And I was curious about your opinions about whether the artists of the era used Theosophy as a springboard to explore other spiritual traditions, or were the specific Theosophical ideas often the most important? Is it very difficult to generalise, or are we seeing some very central, strong themes?

James: I’ve got a thought about that which I can start off with which is: it’s interesting, actually, that the exhibition was called Mysticism rather than Theosophy, so we did go back to putting Theosophy in the title of the book to show that it’s really at the centre of what we were doing. And I think probably the reason for that, from my perspective, is that when it comes down to it, Theosophy was particularly attractive to artists because so much of what was discussed in Theosophical texts was to do with experience, and the senses, and for want of a better word, aesthetics. A text like Thought Forms is important both because it was spiritually challenging but also because it had something directly to say about representation, the senses, the arts, the importance of the artist. And so I think artists in particular (including musicians and filmmakers and so on in that category) were interested in Theosophy precisely because it opened up new ways to think about their art forms. I mean there are other kinds of traditions of religious esotericism in the book and that were obviously working alongside Theosophy; but when you look at what’s really driving the artistic experimentation, I think most often what you see is an influence of a text like Thought Forms, ideas that were coming through Theosophy that were specifically about the importance of art and the artist in generating new spiritual insight. And so I think that’s why Theosophy is at the heart of it, because it did have a place for the artist, it had a central place for the artist in fact, and it had a central place for the experience of art forms and of sensory information more generally as a prompt for new spirituality.

Chris: If I could add to that too: you know the West Coast of the United States, or the Western part of the United States, was identified in Blavatsky’s writings as being a central locus for the development of humankind in the future. And historically we can see that as a kind of magnet to people who were sympathetic and interested in esoteric ideas, especially Theosophy but not just Theosophy. And we can talk about Theosophy in the Western part of the United States, but as that had its moments and died down, we can see subsequent waves: the New Age, and other things, being very prevalent in that region. And if we wanted to, we might connect those ideas to this initial identification by Blavatsky about the West Coast being a place of power for those kinds of beliefs. And when we have a bunch of, as we showed in the exhibition and the book with these maps, all of these people moving to the Western part of the United States, it would seem that they’re not all card-carrying Theosophists, but they think that the West is where occult powers are manifest. And so we find a number of different influences that are kind of like resonances of that initial Theosophical identification happening through the artistic world.

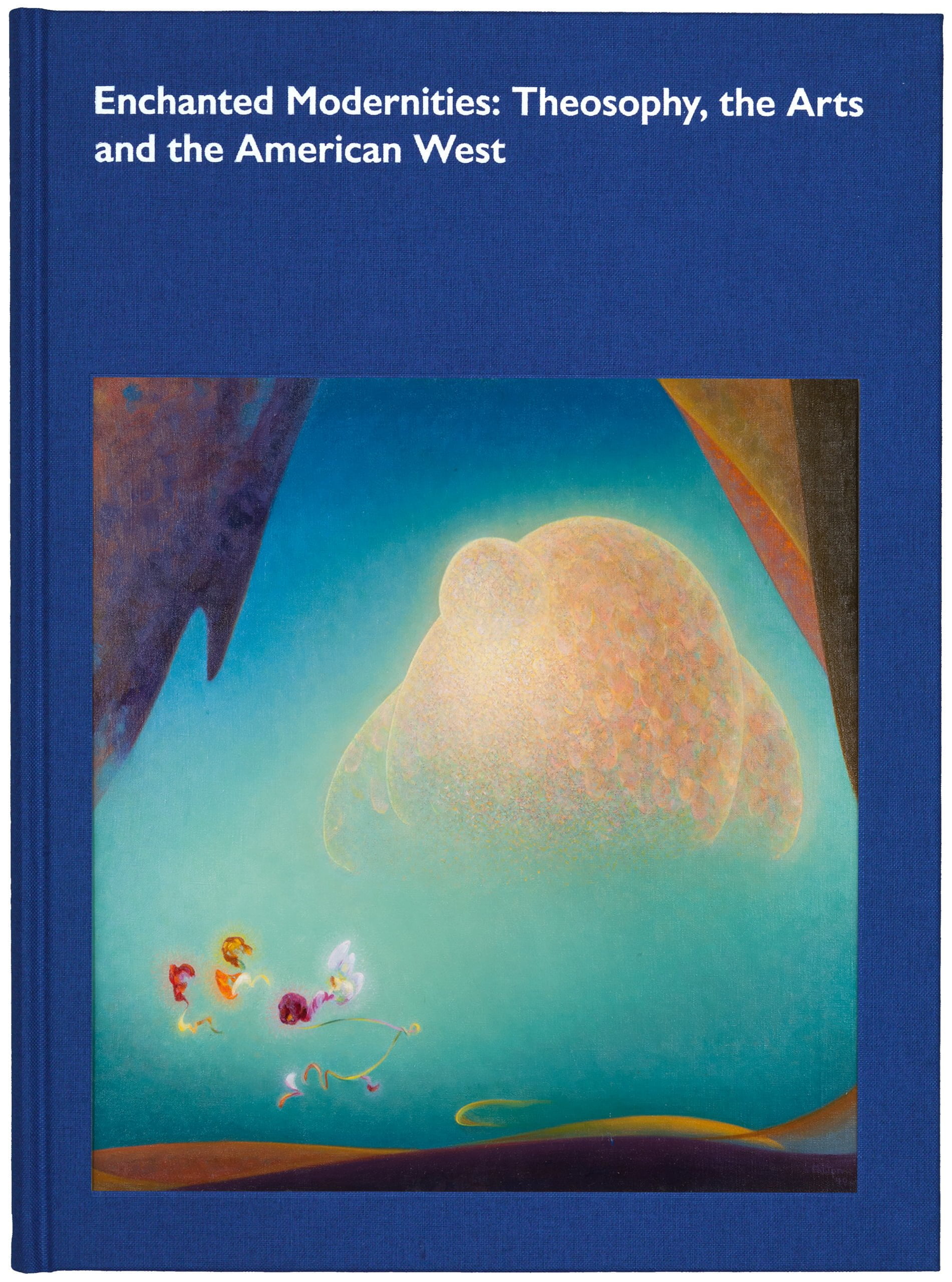

Sarah: We did look at specific case studies of artists, and as Chris said looking at their movement West, and what drew them to that particular area. Agnes Pelton is one of the artists that springs immediately to my mind, and we have one of her paintings beautifully reproduced on the front cover of the book. Interestingly, she’s going to have a big show, it’s opening soon in Arizona and then moves to New York in 2020—so it’s kind of indicative again of this rise of interest in some of these artists that we’ve included in the book. But Pelton as well was really fascinated between the analogy between sound and colour, and some of those ideas which Theosophists and Theosophical texts gave particular import to: ideas about synaesthesia and the correspondences between sound and sight and particularly colour. It’s really apparent in her work and the sketchbooks that we’ve also reproduced in the book, and in several essays, one by Anna Gawboy who’s written about Pelton and the musicalisation of colour, and then another by an art historian called Rachel Middleman as well who looks at Theosophical texts alongside Pelton’s paintings. So I think it’s quite interesting: we can talk quite broadly about these ideas, but also we have tried to pin it down as well, and give people some case studies of artists where we can see these ideas be made manifest through the materials that they use and the art forms that they make as well.

EH: Speaking of specific art forms, Anna Gawboy writes that there is a ‘long tradition that considered music the most spiritual of the arts because it conveyed its message directly to the hearer without the mediation of representational images or words’ (p. 72). I was wondering if, at the time (and I’m going quite specifically here), was there some kind of ‘artistic hierarchy’? In other words, is music the most pure art form? Was that the general consensus amongst artists? Or was what was depicted considered to be the most important, or how it was depicted more important? Were these conversations going on at the time? I was just very intrigued by that, because pointing to music as being the most spiritual of the arts—I can understand it, but I wanted to know if that was a narrative at the time.

Chris: There’s definitely in general a romantic tendency to look to music in the visual arts and in the literary arts in the late 19th/early 20th century as an inspiration, because of the perception that its abstraction allows a less mediated emotional connection. But at the same time, and I think maybe James and Sarah will have something more to say about this, for the people we’re talking about, vibration is a key idea. And the way it is interpreted in books like Thought Forms and elsewhere is that music is vibration, and that visual art is also vibration, and so it’s two versions of the same thing. And so it’s about the nature of the effect of the vibrations upon the person.

EH: Vibration through colour, specifically, or through form and line as well?

Chris: Well, all of those–form and line and colour are all discussed in Thought Forms, and that book is so influential on those kinds of ideas; and it ends with three depictions of musical works, making that kind of connection overt.

EH: Right, these sort of castle forms.

Chris: Yes, so supposedly a piece of music is played on an organ in the church at the bottom of the painting, and the abstraction pictured above represents a visualisation of the music, which is supposed to have the same vibratory quality as the music itself.

James: More generally, there is definitely an interest at this time in both hierarchies of the arts and interconnections between the arts. I wouldn’t say that there was a single hierarchy that placed music at the top, although there is a cultural tradition in that regard; but I’d say more generally, in the context of modernism, there is a debate about the various values of the different arts, and different thinkers and different artists come to different conclusions. And I think Theosophy is quite specific in the kinds of conclusions it comes to and therefore the kinds of influences that it has. I think it comes down specifically to what Chris has just outlined, insofar as the differences that we perceive with our secular senses between music and the visual arts are actually produced exactly by those secular senses (in Theosophical thought). And the point for a number of the artists and thinkers involved in Theosophy and included in the book was that actually if we were to bring the art forms together, we would develop new ways of perceiving the world that didn’t put up those artificial barriers between the arts.

Sarah: That idea of trying to find new ways to see the world and depict the world is really what’s at the heart of a lot of the work of these artists. You can sense that there was something of a frustration with the traditional forms of art that they’d learnt at art school or musical school or conservatoires etc. A lot of the artists we include in the book turned away from the historic traditions of figuration and realism and representation. And what we do see in this kind of dialogue between the arts is this emphasis on abstraction, and how to represent spiritual awakening, and the idea of new knowledge, of acquiring revelation, of acquiring this knowledge through forms that are not traditionally representational. And I think that’s the role that abstraction comes to play, whether we’re talking about music or the visual arts, even the literary arts as well: there’s that emphasis on that colour, and form, and their interrelationships through different shapes, it’s as if they’re being put into different conversations with each other can create new meanings that can give people access to spiritual knowledge. And so I think abstraction becomes a really key term and a key way of thinking and working in the early 20th century—which again has been seen as a purely formal experimentation, rather than having these kind of wider connections, these connections outwards to the wider world and these conversations that are happening within philosophy, within religion as well. So that for us the kind of exciting job that needed to be done: to connect up these artworks with this hubbub of discussion and debate in the early 20th century.

EH: One of the contributors to the book, Paul Ivey, makes a point about using art to conjure mystical awareness through music instead of merely depicting it (p. 36). There’s a difference between these two: one is to allow the hearer or the audience or the viewer to experience a mystical state through the artwork, and the other is to merely depict. I wonder if any of you would explore the distinction of these two functions to the artists of that era and say which one was considered in a way more pressing or important. Was it more important to bring people to a mystical state, or to depict what the artist as mystic was perceiving?

Sarah: I think in terms of a lot of the artists (I’m using that term very broadly) that were included in this book, their mission was not a didactic one. Because they were participants in a sort of journey of spiritual learning, I think they wouldn’t want to present one option or one lesson through their works, but see the viewer and the audience for their work as participants, or potential participants, in this kind of process of learning and acquiring new esoteric knowledge. But I’m speaking very specifically about, again, the artists in the book; I’m sure there are other cases where we can point to a much more didactic mission through their work.

James: There is a quote from Thought Forms, about the plates and the extent to which they successfully manage to reach the kinds of visual forms that truly represent the states they’re intending to represent.

Sarah: Yes, they say that when you have to make do with the materials of the earth you can only get so far…

James: …and I think from my perspective, for the kinds of people I’ve researched, I would say it’s more important to them to have a vibratory impact, rather than to represent spiritual realities, it’s about transformation, it’s about transformation of perception. So to give an example, and Chris might want to add to this, in musical culture the interest in the quartertone or microtones in general, it seems to me is not really about representation but to have an impact on the hearer that causes them to sense differently. Some composers were interested quartertones precisely because they thought they were transformational: when you heard it, you began to perceive differently. And it was something that Oskar Fischinger said directly about some of his films, that he intended them to have an impact on the optic nerve. The films weren’t meant to be a representation of anything in particular—they were intended to cause new kinds of perception, new more spiritual kinds of perception.

Oskar Fischinger: Blue Cristal, 1951. Courtesy of Utah State University.

Chris: We have to think also that there was probably a sense of who the viewer was: who is going to be looking at these paintings and listening to this music, and what their abilities would be. I mean this is talked about in Thought Forms as we just discussed: you have to have the ability to sense these deeper meanings, or ideas, or the deeper vibrations, and you may not have that ability. But that doesn’t mean you’re not getting something from simply having a vague sensation of the kind of exterior of the work, if that makes sense. I can think of one example musically that might be a helpful parallel: and it’s a piece that was played as part of the concerts for the exhibition. There’s a piece by John Foulds, the three ‘Aquarelles’, each of which is based upon a painting. The second one is ‘By the Waters of Babylon’, based upon the William Blake work. And he (Foulds) uses quartertones, as James has been talking about, in this piece. And there’s very much a sense that the music is presented and then through the integration of quartertones kind of dissolves away into something else, as if you’re almost looking at the surface of the painting and then going through the painting or something like that. It’s something similar, and—Sarah you may have to save me here—but I seem to remember Agnes Pelton talking about that, talking about the surface and the interior when she was discussing her paintings. Am I just kind of having a senior moment?

Sarah: No, no, and those ideas were particularly important for the group she was a part of, the Transcendental Painting Group.

Chris: Yes.

Sarah: And again, because of their deep and sustained conversations with Dane Rudhyar, were interested in this kind of idea about how to ‘penetrate the veil’, I think that was the phrase that was used. And so thinking about the surface of the canvas in particular, how could you get through that? How could you permeate its materiality and enter into another realm? And so I think those ideas were particularly significant for the TPG.

EH: I’d like to end with talking a little bit about the impact of the project and what you believe the impact has been, what the response has been? It’s been going on for some time now, so you’ve been working on it for some time: how would you summarise the impact?

Sarah: There’s so much to say there. I guess for all of us it’s personal and professional. I think for me, again from my vantage point as an art historian, going into a major institution, like the Guggenheim, and seeing Theosophy openly discussed on the captions for a public audience is quite incredible. I’m not saying we had a direct impact on that!—but I think our project is part of this cultural shift in thinking about the wider importance of spiritualism, esotericism, and all its associated movements. So just seeing and feeling that the project is part of something bigger, and this book contributes to a much broader conversation globally about the ways in which we write history and the narratives that we tell about artists. It’s something that’s incredibly gratifying and exciting to be part of. On a personal level, the people that we’re talking to now have become such incredible friends, and that also goes for the people in the network, and just the conversations and the connections that we’ve made have been truly enriching intellectually, but also personally.

James: From my perspective I think only time will tell. There are certain people in the academic world that are very open and receptive to this kind of research, but I still think there are plenty of people who are quite hostile to it. Lots of the work we did in this network fed into work that I published in my own monograph on noise, and the response to that has been really interesting. The second chapter on Theosophy has been the most commented upon, and it’s provoked two separate reactions. One is to say ‘that’s the most interesting part of the book, that’s so fascinating and different to what I was expecting a book on noise to be about’, and the other response is ‘I don’t want to read about this, I really don’t want to know about this Theosophy stuff, it’s really unpalatable’. So I feel like there’s still quite a polarised response to this kind of research: people who don’t want to know, and people who just find it fascinating and surprising. So I think time will tell whether it becomes a more mainstream part of the way that we research modernity, modernism, and the arts.

Sarah: I was going to say James, art historians are honestly a much more embracing bunch!

James: I could quote some reviews of my book. One reviewer said something like ‘I spent far longer reading about Theosophy than I’d ever want to have done’!

Sarah: Let’s hope they don’t get a copy of this book then!

Chris: I think that the growing attractiveness of these narratives and this art to a wider public says something about where we may be headed, with the Hilma show at the Guggenheim, and other shows now popping up all over, which seem to meet this topic kind of head-on, rather than putting it in footnotes or not mentioning it at all. It’s really exciting to watch that. And who knows if we contributed to that. But if nothing else, our book will hopefully contribute to a more complete understanding than has hitherto been had of these artists and these times that we’re trying to research and study. I mean, a little anecdote: this stuff is obviously becoming more mainstream and more popular. I was in IKEA the other week, and you could buy Hilma af Klint prints. So that says something about the growing awareness and growing demand for this kind of art, even if—maybe if they’re buying in IKEA they don’t know the whole story behind it, they just like what it looks like, but still, that would maybe never have happened five years ago.

EH: Great. It might be through the consumer culture, but hey, at least it’s coming in…

Chris: Well exactly, and maybe someone will then go say ‘well who’s Hilma af Klint, or who’s Agnes Pelton?’ or whatever. And then the narratives they find will be these narratives, or there’s something there for them to read, whereas maybe there was not so much for them to read ten years ago.

James: I have a feeling that up until a certain point, being openly Theosophical or esoterically spiritual was a barrier to acceptance for artists and musicians, and I think that has changed. And Hilma is a good example. And there are others I can think of where what would be viewed as an unacceptably strange or unusual worldview was a barrier to mainstream acknowledgement, and I think that has changed. Just because you had unconventional views as an artist no longer means that you can’t be widely celebrated and known and shown in galleries and performed in concert halls. That’s something that has changed.

Sarah: And I’d say that actually it’s working the other way, that for contemporary artists who are interested in the occult and the mystical, it guarantees them in a way another audience. I’ve just noticed when working with contemporary artists how they’re not embarrassed to state that they’ve got an interest in esoteric ideas, and that’s been a definite shift within the contemporary art scene, to being very open and almost encouraging of what might have once been seen as that subcultural or counter-cultural interest as well.

EH:And it may be that contemporary art has had a role to play in making it more acceptable in academia.

Sarah: Yes, I think that’s right, definitely. Can I just add one thing about the book as well? As an object, as a material thing, we were really delighted with the way that Fulgur took on the project. We could see that the image quality, that the materiality, the quality of the printing really mattered to make our argument really sing about the visual and material qualities as works of art. So we were really pleased about that, and that dialogue that we had with Robert Ansell about the book’s textures and the way that he really played with those ideas and incorporated them into the design of the book. Because I don’t think we would have got that kind of interest in those ideas if we were working with a conventional university press, for example, where often you’re forced to have black and white images, or you have to get huge subvention. It seemed really important that the book was part of the argument itself, in its material and visual form. So actually having it in our hands and opening it up and seeing photographs of the cracked desert on the fly leaf and then you open it up even further and you have these incredible gate fold images: Andrew McAllister’s photography, another contemporary artist we’d worked with on the show and for the book. He’s got an incredible image, an almost panoramic image of Church Rock—and how Robert incorporated that physically into the book has been really exciting. I don’t think I’ve ever made a book or worked on a book quite like this.

EH: I’m so happy to hear that, it’s delightful, and it really is a gorgeous book!

Sarah: We’d just like to say thank you to Fulgur!

RELATED PRODUCTS

Enchanted Modernities: Theosophy, the Arts and the American West

VARIOUS CONTRIBUTORS

Edited by Sarah V. Turner, Christopher M. Scheer and James G. Mansell